The UK economy is holding up but the housing market remains vulnerable

The UK economy is doing better than forecasters expected at the end of last year. The biggest short-term risks are sticky inflation and higher rates, which could negatively impact the housing market. However, consumer confidence and the business outlook have improved recently, even as recruitment challenges in the form of skills shortages remain.

The UK short-term outlook is better than expected

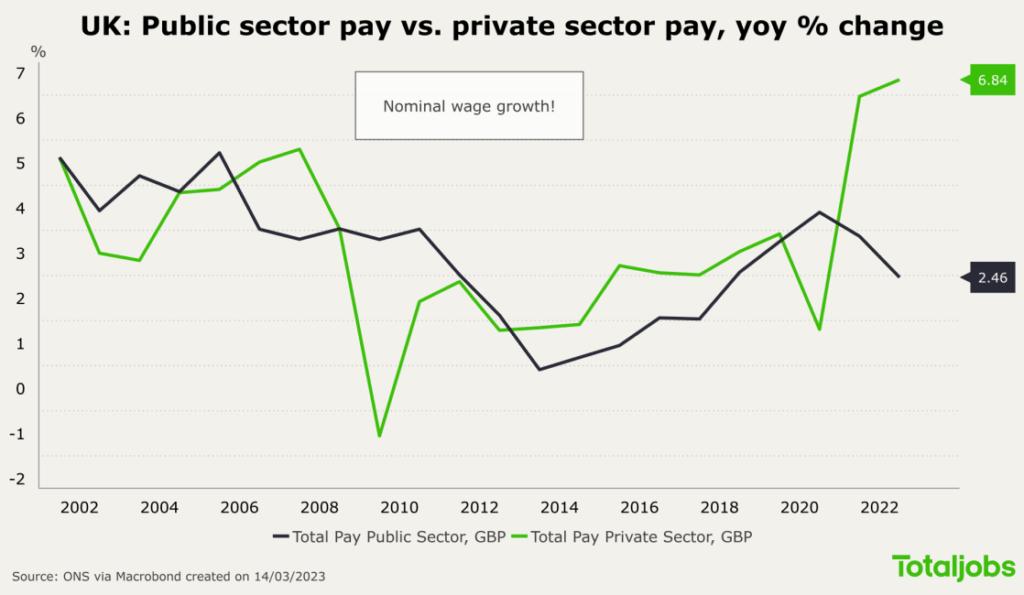

Last year was a challenging year for UK workers. With the commodity price shock resulting from the war in Ukraine, inflation reached a record-high of more than 11% at the end of last year. Meanwhile, private sector wages only increased by some 7% and public sector wages even less, meaning that the majority of UK workers saw their inflation-adjusted or ‘real’ wages go down. It is thus no wonder that many workers are looking for a different job with higher pay.

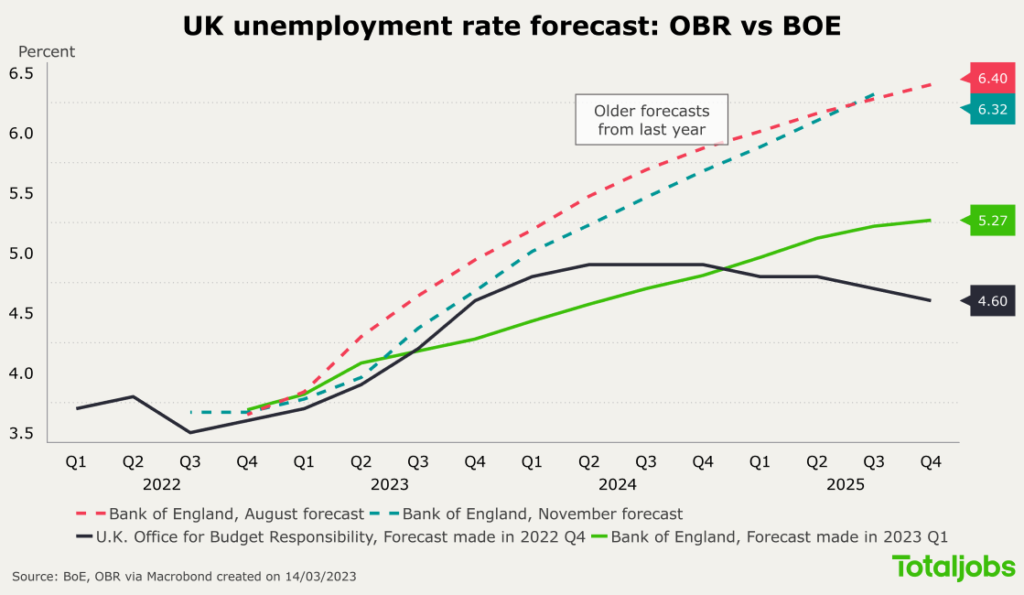

At the start of the year, the Bank of England (BoE) was forecasting a severe and long-lasting recession for 2023 and beyond. More recently though, the BoE substantially revised the near-term economic outlook. The UK economy will most likely fare better than previously expected now. The baseline assumption for the first half of 2023 is a shallow recession with only a modest increase in the unemployment rate this year. Both the BoE and the Office for Budget Responsibility are now forecasting a peak unemployment rate of about 5% in 2024, followed, however, by a rather timid recovery.

The near-term growth outlook has thus improved from what forecasters expected just a few months ago. Moreover, hard economic data has generally surprised on the upside. Similar to the US and Germany, soft economic data in the UK was suggesting a very nasty downturn for quite a while, but actual economic figures like GDP growth, employment, and consumer spending have not corroborated that story.

As I recently argued, the UK is missing a lot of workers, mainly for two reasons. First, there is a shortage of manual workers due to Brexit. Second, about half a million people have left the UK workforce due to health reasons and economic inactivity in the UK is rather high compared to other advanced economies. It is therefore quite likely that the UK labour market will not suffer that much even as the economy will fall into recession in the first half of this year.

Google trends data shows that worker shortages are still a concern for businesses. Google search queries for the term labour shortage are still elevated compared to 2020.

The economy is vulnerable to a negative shock in the housing market

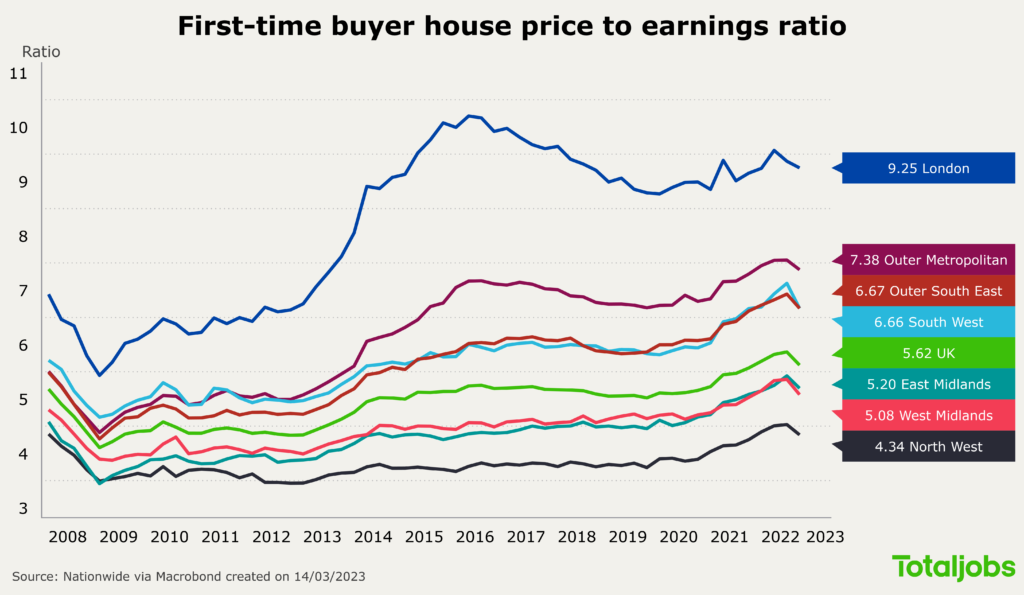

However, some vulnerabilities remain in the macroeconomy, and the biggest point of concern for the UK is probably the housing market. New research shows that the UK housing market is one of the most precarious among advanced economies in terms of housing affordability. Large cities in the UK score particularly badly in terms of price to income and rent to income ratios, with Greater London obviously being the epicentre of unaffordable housing.

The following chart displays first time buyer house price to earnings ratios for various regions in the UK. Two things stand out in particular. First, price to income ratios have generally gone up significantly across the UK due to a broad housing shortage. Second, and unsurprisingly, Greater London stands out as particularly unaffordable. However, the region also has the highest median income in the UK and the deepest labour market.

In that sense, unaffordable housing is probably one of the largest obstacles to more growth and job creation as it prevents workers to relocate to the cities where the most job offers are. If the additional expense for housing eats up more than what you can get in higher wages when relocating, it does not pay off to move to the unaffordable cities even if the labour market is deeper and might offer better job prospects.

Fixing the housing market would go a long way in addressing worker shortages for manual jobs for which working remotely often simply is not an option, such as the hospitality industry. These workers have been priced out of expensive cities in recent decades and face increasingly long commuting times.

In the short-run, there is a risk that house prices might fall substantially, but for the wrong reasons. If inflation turns out to be stickier than the BoE expects, or if there is another commodity price shock driving up prices, the BoE will have to respond to that by keeping its policy rate higher for even longer than markets are expecting right now.

House prices are already weakening as the BoE’s policy rate has increased by more than 4% in 2022. This has led to a significant surge in mortgage rates, and with a large share of UK mortgages being flexible, mortgage repayments are surging as well.

For the first time in more than a decade, it is now cheaper to rent than having a mortgage, according to Bloomberg. House prices have fallen very little so far, but transactions have declined quite significantly. The big risk is that the BoE would have to respond to higher inflation with even more rate hikes, which would leave the housing market dead in the water.

A negative wealth shock from rapidly falling house prices would depress consumer spending, which in turn would have a knock-on effect on the economy and weaken the labour market.

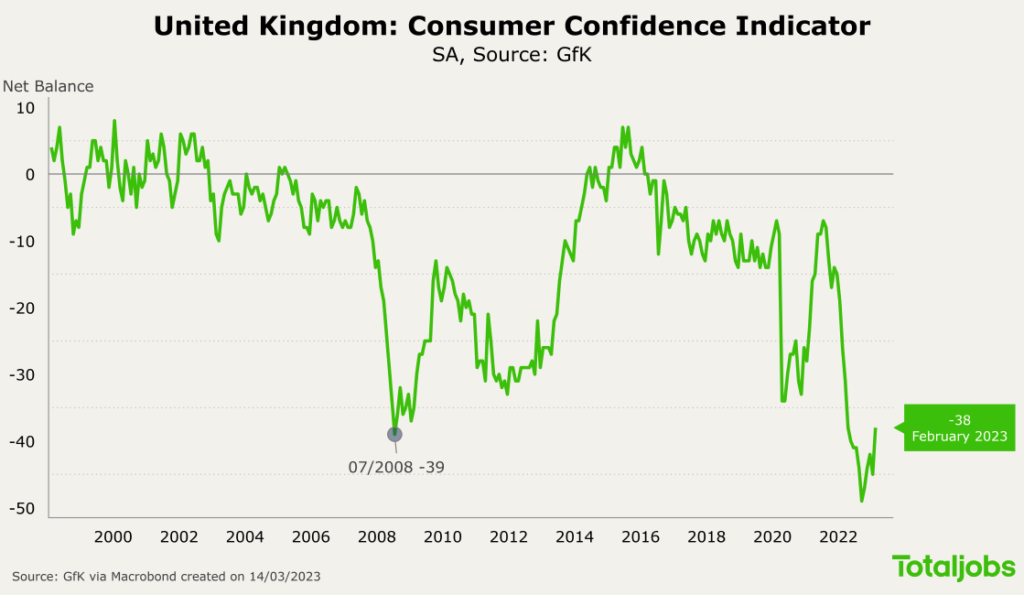

Consumer confidence and the business outlook are improving though

Luckily, the inflation outlook at the moment is taking a turn for the better, which means that additional interest rate shocks that could kill the housing market become less likely. Moreover, consumer confidence is also bouncing back nicely, albeit from a historic all-time low.

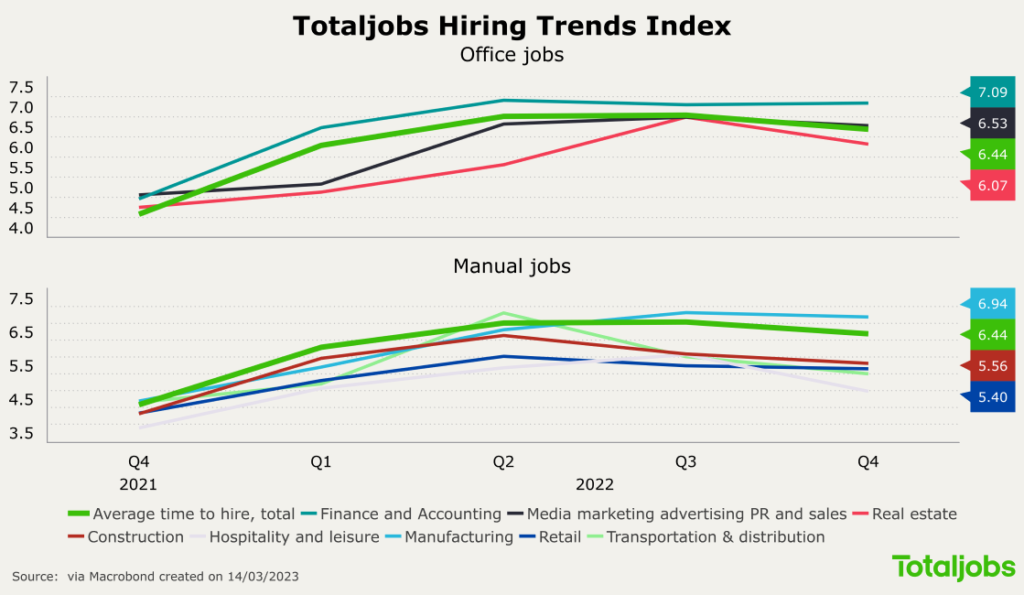

The recruiting outlook is improving as the labour market is normalising. Last year, companies had extreme difficulties filling positions. Our Totaljobs Hiring Trends Index shows how the average time to hire across all sectors (the bold green line) increased significantly from about 4.5 weeks at the end of 2021 to more than seven weeks in mid-2022.

The last two quarters of 2022 have seen gradual normalisation with the average time to hire decreasing for manual jobs in sectors like construction, hospitality and leisure, and retail, for example.

For office workers in media and marketing, finance and accounting, on the other hand, recruiters are still finding it difficult to fill positions. The average time to hire remains comfortably above six weeks compared to four to five weeks in 2021.

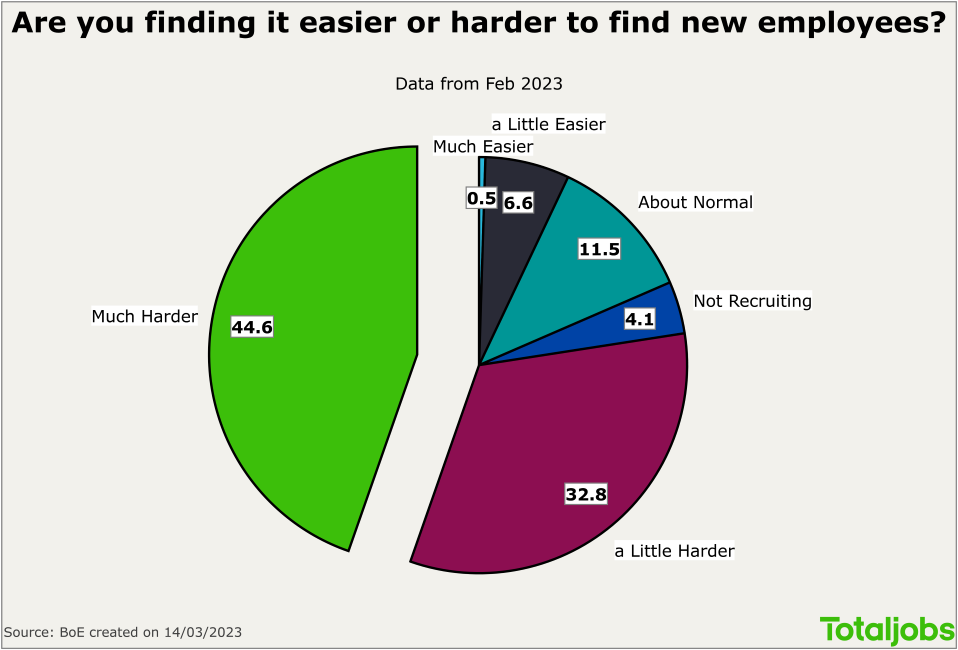

Data from the BoE confirms that companies are still struggling to find new employees even as the labour market is getting back to normal. More than 44% of recruiters are finding it much harder to find new employees.

The situation has already improved compared to 2022 though when more than 60% of respondents found it much harder to hire. The labour market is thus slowly getting back to normal.

One of the biggest long-run challenges that the UK is missing workers. The share of the inactive population in the UK has been rising and is high compared to other advanced economies. The participation rate has been stagnating since the beginning of the pandemic.

Getting back those missing workers would be one of the best ways to spur economic growth in the UK. Housing affordability is key since unaffordable accommodation is one of the largest obstacles to a better-functioning labour market that works for all workers.